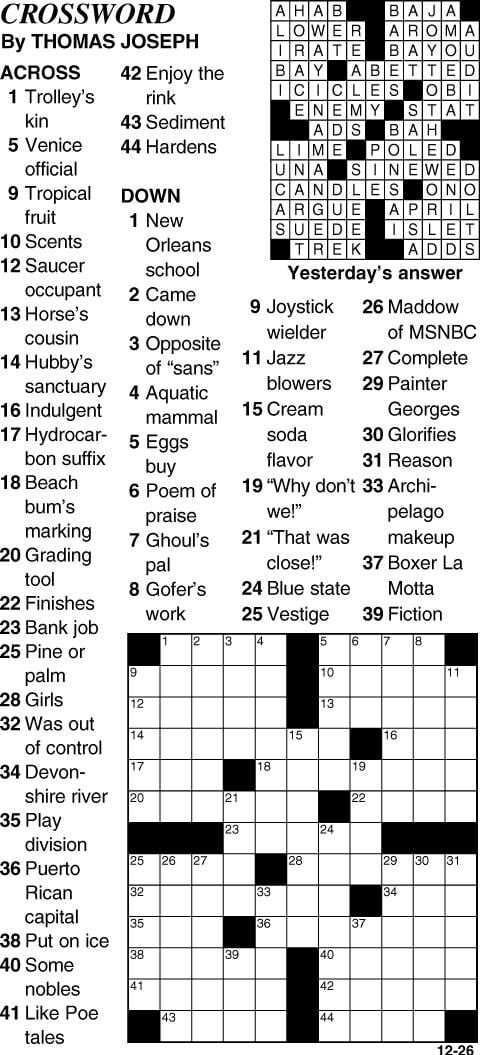

When he plotted out a “Wordplay”-themed crossword onscreen, using grid paper and pencil, I internalized the puzzle’s protocols: perfect one-hundred-and-eighty-degree symmetry, elegantly interlocking words, a minimum of black squares, no jargon or linguistic waste, only “good words.”

Article about crosswords crossword code#

But with his simple puns he seemed to be accessing something foundational about language-a code that could be rearranged and manipulated through sheer brainpower. The hard-core kitsch aesthetics of Reagle’s life were not exactly what drew me in.

Article about crosswords crossword full#

That’s ‘No, a Shark’ !” His house is full of crossword paraphernalia: black-and-white ties, mugs, and a crossword mural in his living room. Later, when coming across the phrase “Noah’s Ark”: “Switch the ‘S’ and the ‘H’ around. “Dunkin’ Donuts-put the ‘D’ at the end, you get ‘Unkind Donuts,’ which I’ve had a few of in my day,” he says. Reagle’s cameo is distinctly unglamorous: we see him in a midsize sedan, driving by Florida’s strip malls, riffing on the roadside signage.

Most of what I knew about crossword construction came from the 2006 documentary “Wordplay,” in which Merl Reagle, the late syndicated puzzle-maker, walks the viewer through the mechanics of designing a crossword. My first crossword puzzles reflected my high-school preoccupations: an early grid was “midterms”-themed, featuring words with “term” in their middle: DETERMINED, MASTERMIND, WATERMELON. I filled notebooks with calorie counts and clues, meal plans and puzzle themes. As I tried harder to escape the trappings of my body-to become a boundless mind-I plunged deeper into a material world of doctors, therapists, scales, and blood samples. A little obsessive, maybe-but the cultural residue of female hysteria, a century later, might have you convinced that this simply meant “adorable.” And, without a doubt, she must be smart. She must be disciplined, I imagined people thinking. “Crossword-puzzle constructor,” I found, was an uncannily compatible identity-container. Diagnoses for mental illness are notoriously reductive, and I wanted to be reduced. It was a distorted fantasy of success that ignored the actual demographic reach of eating disorders and betrayed the stony limits of my teen-aged imagination. I found in the common identifiers of the disease-extreme thinness, perfectionism, a penchant for self-punishment-a rigid template on which to trace my pubescent identity. I read in a health-class textbook that high-achieving, affluent young white women were the population most likely to succumb to anorexia. The connection between these impulses felt intuitive: they both stemmed from a desire to control my image and to nurture a fledgling sense of self. I began writing crosswords when I was fourteen, which is also when I began starving myself.

It was this paradox-the promise of control and transcendence-which first drew me to the prototypically modern grid: the crossword puzzle. “The grid’s mythic power is that it makes us able to think we are dealing with materialism (or sometimes science, or logic) while at the same time it provides us with a release into belief (or illusion or fiction),” Krauss wrote. In 1979, the art critic and historian Rosalind Krauss wrote about the ubiquity of the grid in modern art, citing the even-panelled windowpanes of Caspar David Friedrich and the abstract paintings of Agnes Martin.

From sidewalks to spreadsheets to after-hours skyscrapers projecting geometric light against a night sky, the grid creates both order and expanse. When not working on a puzzle, David can be found reading his favorite daily comic strips.A grid has a matter-of-fact magic, as mundane as it is marvellous. Additionally, David is a frequent attendee of crossword puzzle conventions and a respected tournament judge.

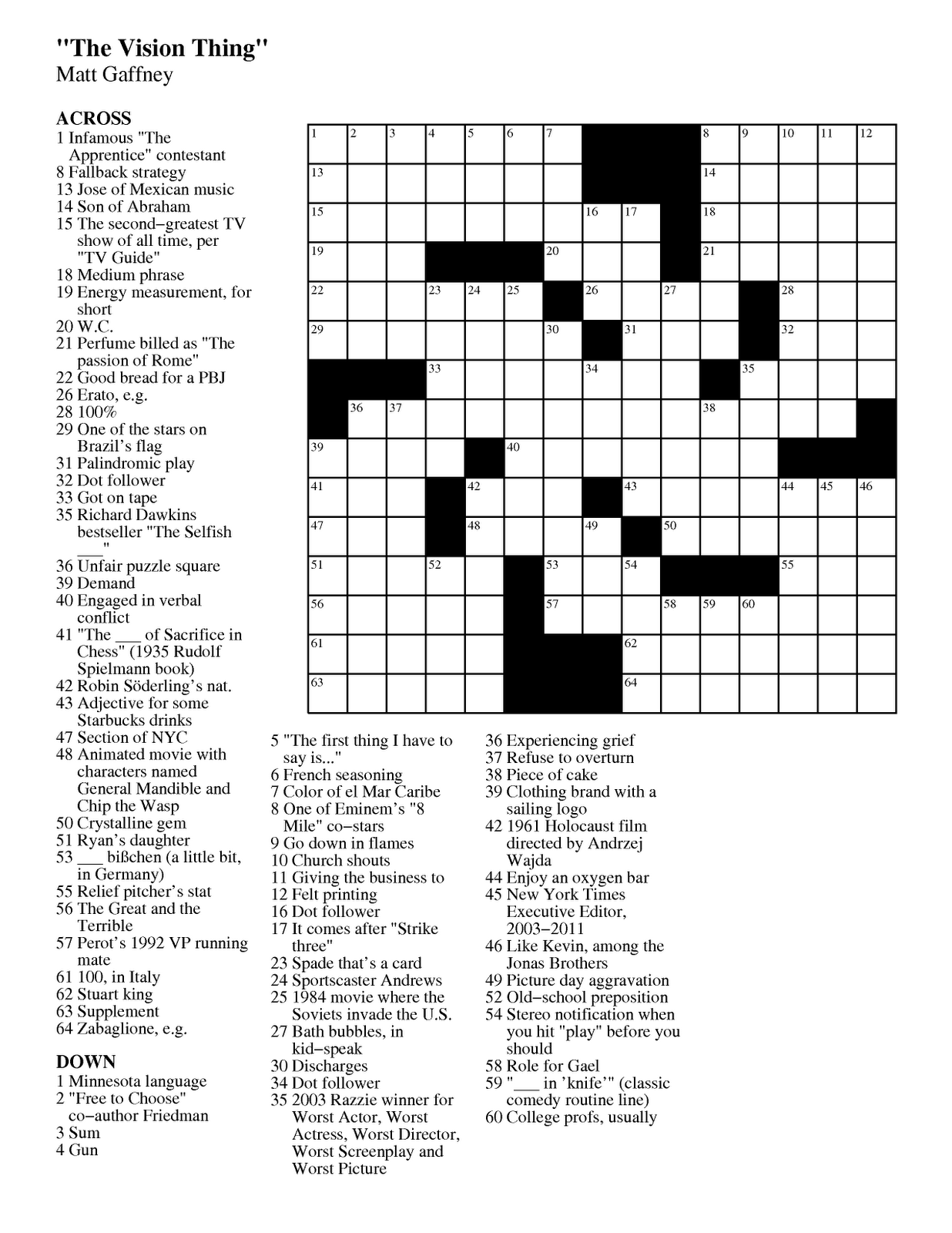

He is the founder and director of the Pre-Shortzian Puzzle Project, a collaborative effort to build a digitized, searchable database of New York Times crossword puzzles dating back to 1942. David is also the author of two books of crosswords: Chromatics (Puzzazz, 2012) and Juicy Crosswords (Sterling/Puzzlewright Press, 2016). He was most recently the editor of The Puzzle Society Crossword. To date, David has had hundreds of puzzles published in the Times and other markets (Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, Daily Celebrity Crossword, The Crosswords Club, The American Values Club Crossword, BuzzFeed and The Jerusalem Post). At the age of 15, David became the crossword editor of the Orange County Register's 24 affiliated newspapers. David Steinberg published his first crossword puzzle in The New York Times when he was just 14 years old, making him the second-youngest constructor to be published under Will Shortz's editorship.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)